“And while they were there, the time came for her to give birth. And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in swaddling cloths and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn….And in the same region there were shepherds out in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And an angel of the Lord appeared to them…and the angel said to them, “Fear not, for behold, I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord. And this will be a sign for you: you will find a baby wrapped in swaddling cloths and lying in a manger” (Luke 2:8-12).

A lot of people talk about “seeking God” as though on some open-ended quest toward an infinite horizon. But when the shepherds, who had just seen the infinite horizon rend with songs descending, were told to seek God, they were also told they would know they were on the right track when they received another grandiose sign from on high: a baby born in a barn.

Some sign…

Oddest of all—

That God became small

We need to learn to become small again too.

Imagine how much bigger and more mysterious the world must have been before it got entangled in the World Wide Web, a world without Buzzfeeds that reduce our ordinary world to a series of tragic or trivial headlines and Newsfeeds that reduce our social world to a series of one-way conversations 140 characters-deep and 10,000 friends-wide. Imagine a world without Google Maps and Google Earth and Google Sky and Google Multiverse (forthcoming).

Imagine what it must have felt like to not feel like you are at the center of the earth or the center of every event and every relationship on earth. Imagine a world with board games and the great big woods outback.

Imagine—remember—what it feels like to be as small as a single man.

Our digital universe makes us feel bigger than we are. We have all-seeing-eye syndrome, miracle grow to an already deeply rooted god-complex, ceaselessly consuming newsfeeds from everywhere to everywhere, taking in the world with unprecedented immediacy and scope, continually finding ourselves having to form positions and make judgments on matters near and far, then and there, on events and outcomes, on catastrophes of both evil and “natural” sorts, on wars and rumors of wars, on futures warned and futures promised and futures feared, on systems of oppression and Whose responsible? and all the reasons I’m not, on the temperature and destiny of the earth, on the policies that should govern a global economy, on the measures taken—or decidedly not taken—in exercising military force in defense of our nation, or in warfare against the nations, and, on that note, on ancient demonic conflicts fought under revolving political pretenses over land and God and honor and greed and vengeance and envy and eschatology. We are in the know of whatever we want to know and the world feels like an extension of our collective, skyscraping fingertips. It is hard to be small when we’ve built the collective illusion of our bigness out of the brick and mortar of a subdued earth.

We are a great civilization, indeed, but we are building in the way of Babel, toward progress, not promise, toward a greater vision of ourselves, even trans-human, rather than God’s vision of us, rather than being conformed to the image of the Son. The notion of conformity violates our ethos of authenticity, since we persist in that age old habit of refusing to be made in God’s image and insisting on making him, and our world, in our own, as we have since Adam, in Adam (cf., 1 Cor. 15). Human civilization continues to advance through the shared will to “make a name for ourselves,” usually under the name of some leader’s or representative’s will, but decidedly not the will of God.

“Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.

—Genesis 11:4, The Tower of Babel

But all Babel’s towers are made to fall. God’s Word reveals history has a definite shape, that it is moving toward a definite end, but in this story history does take a cyclical shape precisely in kingdoms rising and falling, towers of trade reduced to tragic memorials, great coliseums left to erode in the wind like skeletal remains of the city’s ghostly soul. The higher a civilization ascends in its heavenly aspirations—cooperating according to a collective will severed from the will of its Creator—the farther and more immanent is its fall to hellish proportions. In Karl Barth’s words, “the enterprise of setting up the no-god is avenged by its success.”

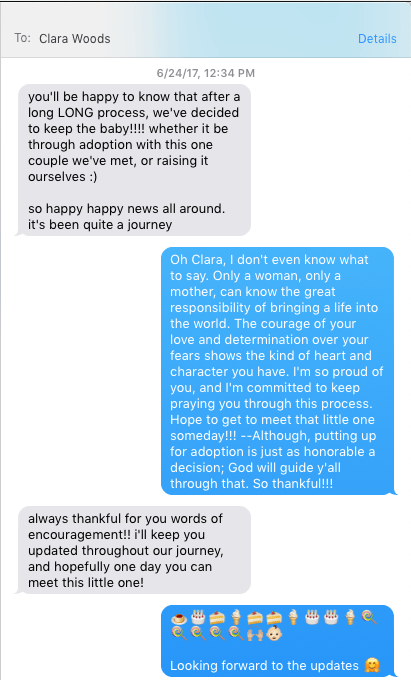

In his Burnout Society, Byung-Chul Han describes the modern Western situation as one in which “everyone is an auto-exploiting labourer in his or her own enterprise. People are now master and slave in one.” He describes an epochal shift social imperative of the zeitgeist as one of a false liberation from a “disciplinary society” defined by prohibitions to “achievement society” defined by permission, from a “you shall not” society to a “be whatever you want to be.” This

“The achievement-subject stands free from external instances of domination forcing it to work and exploiting it. It is subject to no one if not to itself. However, the absence of external domination does not abolish the structure of compulsion. It makes freedom and compulsion coincide. The achievement-subject gives itself over to freestanding compulsion in order to maximize performance. In this way, it exploits itself. Auto-exploitation is more efficient than allo-exploitation [other’s exploiting you] because a deceptive feeling of freedom accompanies it. The exploiter is simultaneously the exploited. Exploitation now occurs without domination. That is what makes self-exploitation so efficient.”

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society

Thus, we now band together primarily to build concrete towers of trade, not temples of human communion, working together to erect edifices that form our social infrastructure of atomization—nuclear fission at the nucleus of the human family—a society that cooperates to enable each member’s self-isolation. We’ve transformed human economy into a digital and materially deliverable faceless exchange of goods and services void of human connection.1 All we have to do is plug in to our respective devices, like rubber nipples in a milk barn, and “consume one another” (cf. Gal. 6) from a distance without ever being released from our stalls—without ever having to meet each other, much less share goods together or feast together or roast weenies together. We’ve transformed human society into a virtual domain in which egos can unite with likeminded ideologues across the globe without ever having to meet their neighbors, much less do the kind of “yard work” necessary to become a good neighbor. We’re forming into digital swarms of common angsts / enemies but have neither the public will to act nor the personal willingness to cooperate to do do anything constructive about it—beyond ongoing doom scrolling and digital engagement: all tribe, no village.

And as long as human civilization is busy building, keeping flashy projects and important “developments” flashing before our eyes, the grand illusion of human progress will continue to distract us from the immediate awareness of human transience, of earthly effervescence, of the inevitability of an end of all things that renders even steel towers as heaping castles made of sand. Our preoccupation in the arena of geopolitical struggle helps us avoid the angst of knowing it all ends in a geocosmic void, knowing that ultimately not one stone will be left upon another, knowing that there’s really no difference between a great city tower and a little mud hut—except perhaps the memories made therein—when you stand back and view them together in light of the whole. Zoom out to the edge of the universe, or as far as you can get just before we (the earth and everything in it) are invisible, and look: there we are, as Carl Sagan aptly put it, on “a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

“A Pale Blue Dot” from Voyager 1, Final Photo

See it? See us? See our tanks and our towers and our triumphs and our treasures? Me either.

And yet, being human—being that same creature that shares the image of the Creator, that shares life and relationship and eternity with the Creator—that is truly significant. But to remember that, we must become small again, we must learn how to become the small part of a big story, supporting character in a grand epic about the Son of God become Son of Man, as Emmanuel—God with us!

But it gets eclipsed by our own shadow. It’s hard to even remember what it felt like not to feel like I was at the center of the earth and the center of every event and every relationship on earth, what it felt like when the whole world didn’t seem like one grandiosely empty extension of my own digital ego

Imagine being as small as a single man?

Imagine being as small as God.

If Christians in America still care about making a kingdom impact on the world, and not just a social or political impact in America, it will be helpful to remember that when God saved the world, he became small. I find it hard to believe this was incidental, as though the Incarnation was just a means to an end to get on with God’s “bigger” plan of a global Christianity so that nations could be built on “godly principles” or “Judea-Christian” values (whatever that means). God became small and called us—commanded us—to descend humbly into smallness with him, and with the children, on pain of damnation (Mt. 18:1).

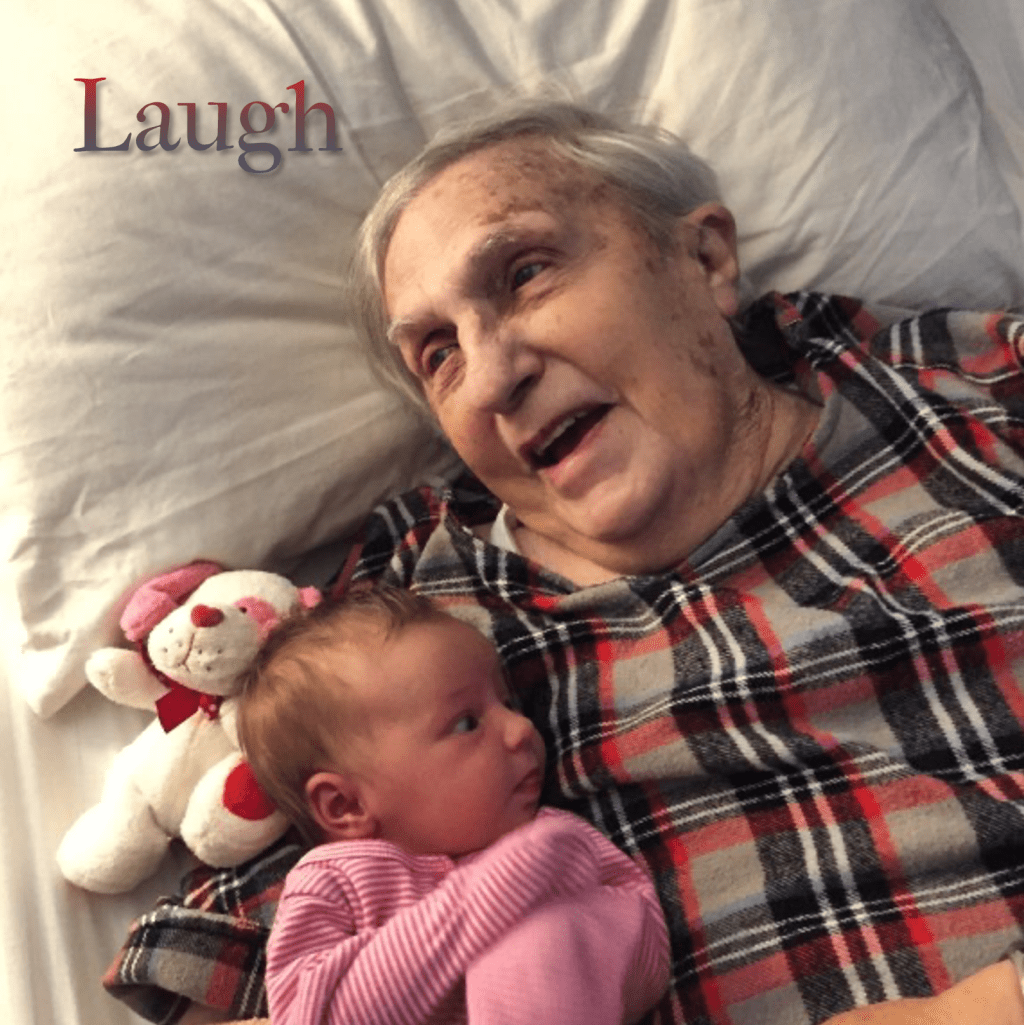

All our nation-building aspirations may be well and good, maybe, but they are not bigger than the revelation that God is a Person who became a Man who put his hands on babies and blessed them, who opened his arms and welcomed us into his family, forever. That’s wilder than the witches of Narnia, crazier than the genes of Percy Jackson. It means that to be human is to be caught up in the divine epic without end, and we may as well still be on page one. Our whole lives in this mortal flesh will be written, and concluded, on page one. All our family trees will splinter off or dry up or burn up, along with the earth (barring some ‘intervention’), on page one. All nations will rise and fall on page one. On the horizon of eternity, everything until the resurrection will come to its end on page one of this eternal epic. So perhaps we need to reconsider what matters most in this big story in which we have a small part to play. What will still matter in a few(?) trillion years, on page two?

It’s the little things. The little things will last. Heavens treasury isn’t filled with the stuff that fills our bank accounts and garages. The Bible says love will last. I guess that’s because people will last and hate will be incinerated. Love is the only thing that existed before anything else existed, the only Thing that will always exist, because God is love and created this universe as one grand arena for his love to be shared. So love will last, relationships rooted in God’s love will last forever. Investing in those relationships seems more transient than investing in real estate, but moth and rust can’t destroy memories in the mind of God. In the end, that’s all that will be left of anything. All creation will one day be a memory in the mind of God, so perhaps the question is What memories does God cherish? Great victories in battles? Political rallies? Family reunions? Family dinner? A mother looking down at the face of her newborn child?

What memories will heaven be made of?

God is not a principle, not even a set of “godly principles,” merely meant to be built on to hold up a nation or all nations like Atlas. He’s a Person, an eternal union of Persons—“God is love”—and the biggest plan of all, it turns out, was to reveal himself personally and unite little people like us into that great big eternal union of love with him. But love is limited in proportion to its capacity to be received. You can’t receive love from a god any more than you can receive love from a government. So God became small, because God so loved this little world that he so effortlessly holds up by the word of his power.

I think the whole idea of God becoming as small as a man was intended to keep men from trying to become as big as a god. Isn’t that what tripped us up in the first place (Gen. 3:5) and has continued to do so ever since the Fall (Gen. 11; Rev. 17-18)? I also think God becoming a Man is the great revelation that stubbornly bestows dignity to every man, every woman, ever child, even the children of our enemies. Moreover do I think that we are in the willful habit of forgetting this basic Christian fact, because it obviously means we should fire rockets at the least of these people with at least a measure of temperance, but probably instead with a terrible fear of God’s inexorable wrath and unrelenting fury, because there is a very real chance he may take it all personally—blowing up babies and the rest—as though what we do unto them we do also unto him. After all, he did become a baby before he grew as small as a Man. And when he was all grown up, not long before he was nailed down, he told us exactly what he would do to all the big people who beat up on all the small people when he comes back all Big again with the fires of hell in his hands (Mt. 25).

But until then, I think this idea of the smallness of God should be regarded as the rule that determines the means and methods of God’s global mission, so that while “Christianity” goes global it never becomes any less personal than Christ was—than Jesus is—himself, according to some bigger, grander, national Christendom project.

This is the troubling thing about people dragging Jesus’ name into political rhetoric, loading up Christian slogans like ammunition for culture wars and social activism. Maybe I’m just being willfully naïve, but I find it hard to believe that the living God who makes black holes and sustains the earth depends on us advancing his kingdom through our violent and compromised geopolitical strategies or culture war attacks.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think it is bad to be concerned with and aware of the global or national scene, especially when you are in a position to do something about it—most of the time, you aren’t—but I’m suspicious of a man who decries world hunger but has never offered to buy a local man’s lunch, who endorses love for the world but doesn’t sit down to eat dinner with his family, who rails against abortion but doesn’t teach his son how to respect a woman, his daughter how to respect herself. The greater are our delusions of grandeur, the severer we suffer the sickness of Dostoevsky’s doctor, who

loved mankind…but…the more I love mankind in general, the less I love people in particular. I often went so far as to think passionately of serving mankind, and, it may be, would really have gone to the cross for people if it were somehow suddenly necessary, and yet I am incapable of living in the same room with anyone even for two days; this I know from experience. As soon as someone is there, close to me, his personality oppresses my self-esteem and restricts my freedom. In twenty-four hours I can begin to hate even the best of men: one because he takes too long eating his dinner, another because he has a cold and keeps blowing his nose. On the other hand, it has always happened that the more I hate people individually, the more ardent becomes my love for humanity as a whole.

~ Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

The problem with following Jesus into his little realm of loving real human beings, the kind that bleed real blood (Jn. 19) and eat real fish (Jn. 21), is that they always get in the way of our ideals of mankind. Real human beings are most hateable precisely in the name of mankind. We hate Hitler so much because we love mankind so much—so I suppose ideals have their place—but is it not that same idealism that can drive me to despise a real live person for eating cereal too slurpilly more passionately than I have ever, personally, hated Hitler? Maybe I don’t hate that person, but I may very well refuse to love him if it means I have to endure his eating habits.

If it is an ideal of mankind we are looking (or fighting) for, we are better off leaving this world to find it. If God himself cannot fix the world without first getting caught up in the thickets of its realism, neither should we imagine an ideal world void of invasive thorns and corrupted crowns, or of some twisted combination of the two. Till God’s kingdom come in all its fiery cleansing, people will continue to erect crosses and blow their noses. And unless we are going to join the effort of the ones holding the hammers, joining the effort of the One holding the nails will always feel small and personal and insignificant, and likely at least a pain in the neck.

The fact is, you can’t make your world any different until it becomes close enough to touch, low enough to look in the eye. That is your world. Everything bigger is a mirage. Anything more important is unimportant, so far as your world is concerned, so far as you’re able to care about it in a way that leads you to care for it. And, paradoxically, it is only in that little insignificant world of yours that you will find boundless purpose and permanence, because it is in precisely that world that you will find the infinite God, who only ever promised to show up to us in the small ways he showed up in Jesus.

Jesus told us plainly where to seek him, and it was not in a temple in Jerusalem, a throne in Rome, a seat on Capitol Hill. He told us, on the contrary, that he would meet us in our gatherings of two or three. He told us he’d make our little gatherings a “city on a hill that cannot be hidden”—cities aren’t nations but can be found in all nations—when we pray in his name, listen in his name, worship in his name, break bread in his name, give thanks in his name, share needs and resources and serve and teach and baptize in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit (cf., Mt. 18:20; 28:16-20; Mk. 14:22-25; Acts 2:42-47). That’s about it.

Although, he did also tell us he would be found in some ways and on some days we wouldn’t even recognize him in the moment. He said he would be present in the kind of places and the kind of people (the “hungry…thirsty…stranger…naked…sick…in prison” kind of people) we’d honestly just rather avoid, which is why he has to command us on pain of judgment (Mt. 25:31-46) not to avoid them, but to stop! to notice! and to see the God-who-became-small in them, even if they always look far more human than divine, because God in the Galilean never looked more divine than human.

The point is this: it’s easier to care about everything and everyone on earth than to care about one single human being. And if we truly care about anyone or everyone on earth, we will make it our business simply to obey the Lord who is sovereign over heaven and earth and do our part helping our neighbors on earth get to know him. At least as far as the Church is concerned, we don’t need to more social or political initiatives than the one we’ve already been given (Mt. 28:16-20). We just need to take the one we’ve been given more seriously. But that requires believing in a very large gap between the size of our efforts and the size of the difference it makes, and it also requires disbelieving in the size of Washington and Wall Street and Hollywood’s depictions of how heroes make a difference (Mk. 10:40-45), so that we don’t waste all our efforts trying to change the one and look like the others or give up altogether because we don’t look like X-Men. Neither did the God-Man.

The kingdom of God is not revolutionary like a typical change in regime. It is far more evolutionary, like a garden. Jesus may not have been as radical as Karl Marx, but he was just as practical as potatoes. Jesus turned regimented religion into a way of living everyday life, where God could henceforth be found at the intersection of human language (called the Gospel) and fellowship meals (called koinonia or Communion). God would no longer be seen or approached at any remove from the ordinary realm of human experience, for he entered into the whole of it—from unborn to dead and buried—and in between he sanctified all the days of our living, the seasons that usher us through life into death, and in Christ out the other side.

The age of the kingdom is evolutionary in the way the age of technology is not. It grows slow. There is a certain size and speed people in America have tended to associate with God that God has tended to dissociate with himself. Indeed, the Gospel frames the divine revolution of God’s kingdom in mustard seed packets. And these mustard seeds are not like Jack’s beans. They don’t magically produce watermelons on vines of Zigguratic proportions. The difference is both bigger and smaller than that—it just depends on how you measure, and I can’t help but think that the American Church’s measuring sticks need about as much conversion as its nonmembers, and almost as much as its members.

Unfortunately or not, the magical mustard seeds of the kingdom turn out merely to produce more mustard seeds (Mt. 13:31), which is precisely the way love works. Loving people in Jesus’ name rarely ever produces mass conversions or a moral majority. Most of the time loving people in Jesus’ name just produces more people who love people in Jesus’ name. And that’s how the kingdom of God has been forcefully advancing for over 2,000 years, in and through and despite the people who call themselves the Church, which has nonetheless outlasted every nation on earth and will alone continue to last when Jesus returns to this earth.

We can never forget how all this began, how not a single member of Jesus’ little lakeside church had a voice loud enough even to cast a Roman vote, and how almost all of them were killed off by the Roman authorities, largely because of the way they were shaping the Roman Empire without the help of those authorities under a different kind of Authority altogether (Mt. 28:18; Acts 1:8). How they managed to function without a cultural pat on the back and a governmental stamp of approval leaves many factions of the evangelical Church as baffled as a camel staring a needle in the eye. But as Jesus once said, it’s easier for the Gospel to get into the Gaza Strip than for Elon Musk to enter the kingdom of heaven—but with God, Maker of Mars and earth, all things are possible. Conversion is still possible.

But we must stop being willfully deceived into thinking that the effect of the Gospel increases with an increase in volume. There’s a reason people tend to avoid sitting next to the guy with the bullhorn, especially if he is carrying a Bible. The Church’s News about the Prince of Peace sounds personal, like an invitation or a confrontation, not like a pep rally. It belongs at the table, not in the bleachers. If we keep blasting it out into the nation-wide airwaves, our best words, like “evangelical,” are going to keep getting bastardized under the jurisdiction of “the prince of the power of the air[waves]” (Eph. 2:2). And that just deepens the mess we’re in now of needing to “unspeak” about Jesus as much as we need to speak about him.

God speaks in a still small voice because that kind of speech requires nearness, and God wants us to speak like him when we speak about him. When we speak about him, we speak about the God who is near in Jesus Christ, and the God who is near in Jesus Christ brings near the kind of people who would otherwise remain far apart in the name of so many other names of so many other tribes and gods and herculean lords-elect. But perhaps we’d rather focus our attention on things bigger than Jesus precisely because we don’t care to be brought near to the kind of people Jesus commands us to love, to disciple, in our ecclesial efforts to build up the international body of Christ (Eph. 4:11-16), which, let’s be honest, sounds so passé against the backdrop of popular Christian culture in America.

These eternal efforts we’ve been given are actually actionable for everyone—unlike all the things our newsfeeds get us all anxious and up in arms about—because people really only need moderate amounts of love to be discipled and built up. What I mean is: people do not need love from the whole human race or even the whole federal government; they just need it from their neighbor, their nearest, and only one at a time. God-sized love can only fit through a funnel that is one-person wide, not because that’s how big the infinite God is but because that’s how small we are, which is why, again, the infinite God became smallest of all.

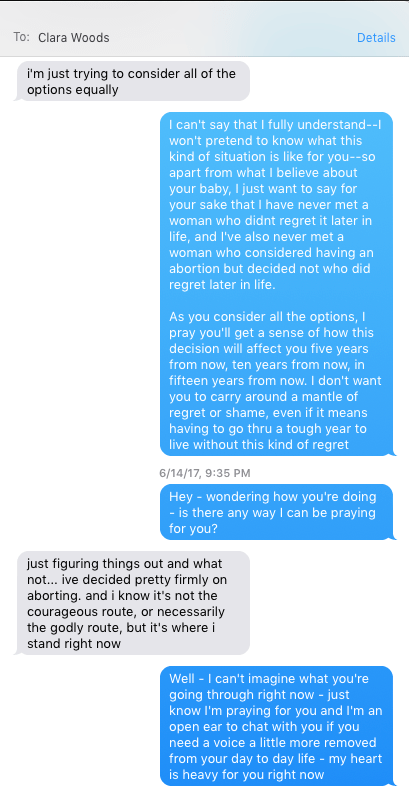

A cup of cold water in Jesus’ name will always be more satisfying than a free drink from the fire hydrant. A pro-life rally will always be less effective than taking a troubled young teen out for ice cream. Protests have their place, but they can’t take the place of the awkward efforts of face-to-face investment, which have personal human impact, where the Word of Christ can be spoken by someone the same size as Christ. Through the Word of Christ, God’s Incarnate love condescends from infinity into the funnel of a human heart by way of the Holy Spirit, the inner life of God flooding into the inner life of a person and producing the living life of faith: “faith comes by hearing and hearing by the word of Christ” (Rom. 10:17). Word becomes Spirit becomes flesh again and again, in miniature. But our big collective efforts with their big important consequences and implications can too readily appease a hostile conscience with the cathartic release that feels more like what you get from going to a Metallica concert than the love you give to that distracted teen who struggles to receive it.

But this is love, this is discipleship, and it can only be measured by its capacity to be received and embraced. So if you want to love an immigrant or a baby, find one. If you can’t find one without a country, find one without home, or one without a father, or one with a father who may as well not be a father. They are everywhere, especially right next door. In the words of Gustavo Gutierrez: “So you say you love the poor. Name them.” Love learns names.

If you want to be “missional” and save the world, just make sure whatever world you intend to save is one inhabited by human beings as real and as small as you are. Even if God sends you across the globe, it will only be in order to send you across the street. But he doesn’t have to send you across the globe to send you across the street, so please don’t wait until you are called overseas to the nations to call your neighbor next door.

God’s global kingdom will always advance through people who are willing to go to the places and people where no one is paying attention, because God cares about the people who are paid no attention, people like you, people like me. That’s what God cares about, and perhaps that’s what we should care about too.

So be small, and know that God was too.

Footnote 1: We never have to meet the people who pick our fruit or sew the soles onto the bottoms of our shoes, for example, so neither do we have to care or be confronted by the conditions they may be enduring to supply our demands to, e.g., eat mangos in December and add another pair of shoes to my pile.