Now while Zacharias was serving as priest before God when his division was on duty, according to the custom of the priesthood, he was chosen by lot to enter the temple of the Lord and burn incense…And there appeared to him an angel of the Lord” (Lk. 1:8-9).

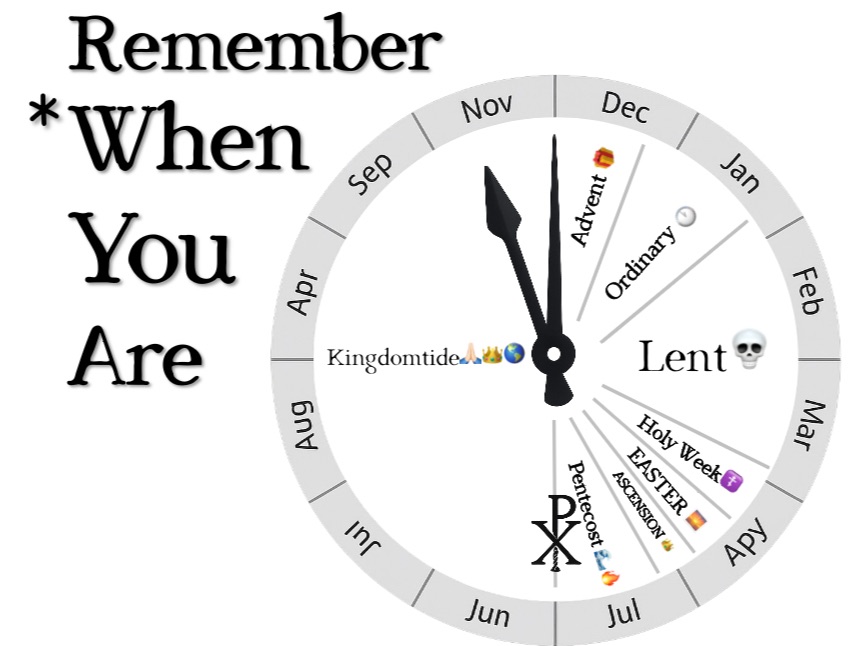

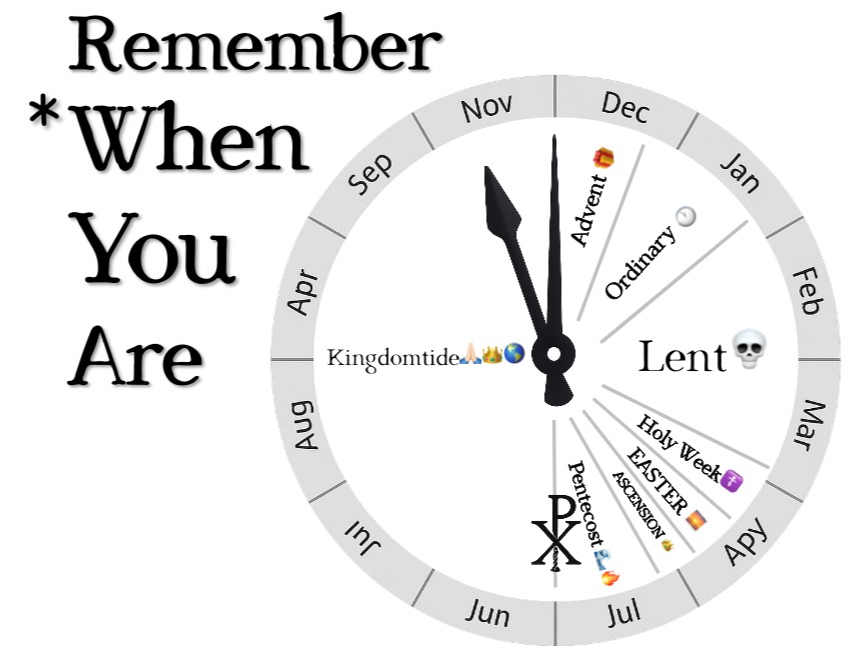

Waiting. Remembering. Preparing. Such was the life of Zechariah the priest. Waiting—because it was still “in the days of Herod, king of Israel” (Lk. 1:5). As long as Herod was Israel’s king, Israel’s King had not come. Remembering—because that was his priestly duty. The priests were tour guides of Israel’s memory. But Israel’s memory was not a museum. Israel’s memory was not only filled with all that God had done but also with all God had promised to do. So the priests were called to be the living memory of God’s promised future. They were called to remember, and so prepare.

There are different ways of preparing. It all depends on what future you are preparing for. A person who prepares for a race runs. A person who prepares for a dinner cooks. A person who prepares for a test procrastinates studies. Indeed, some ways of preparing for the future are better (or worse) than others. Martha Stewart once prepared for the future by selling her shares in a stock, for better or worse.

I suppose by a certain stretch of the imagination Zechariah’s preparation was something like Martha Stewart’s. He’d been tipped off. He knew where to put his stock, and where not to. He knew not to put any stock in the kingdom Herod was trying to build and prepared instead for the one God had promised to bring. But how does one prepare for that—a promised coming kingdom?

Jesus once said, “One who is faithful in a very little is also faithful in much, and one who is dishonest in a very little is also dishonest in much” (Lk. 16:10). I suppose preparing for a promised coming kingdom is all about the “little things”, being faithful in the “very little” of today because God is taking care of the “very much” of tomorrow. Believing that God is taking care of the big things frees us to live small lives of everyday faithfulness.

Zechariah lived like that. He wasn’t known around town for much of anything. Just another priest, not even the “high” one. But he was known by God. Luke said he was “righteous before God, walking blamelessly in all the statutes and the commandments of the Lord” (Lk. 1:6). That may not make the headlines in our nightly news, what with all the big and important things being reported, but God took notice. God takes notice of everyone who lives “before God” (Lk. 1:6), who prepares for the future by living for the One who promised to bring it.

If faith were an arrow, it would not be pointing up. That is the popular way to think about faith, likely because up never leads back down to earth, where my boss and my habits live. Faith is far more comfortable in the clouds than it is on Monday morning. But faith is a forward arrow (Heb. 11). It doesn’t point to an ideal. It points to a path. Jesus didn’t say fly away with me. He said follow me. He said, “Lo, I will be with you on Monday” (Mt. 28:20, paraphrased). Faith is found in the “little” things, like my attitude at the office, or at home where only my family and God have to put up with me. That’s where my faith lives, or not. If we are going to prepare for the coming of Christ, it won’t be up there with my exceptions but down here with my rule. It’ll be on Monday. Jesus is coming back on Monday.

Zechariah was caught “walking blamelessly” through everyday life as he headed to the office that Monday morning. You can tell it was a Monday because Luke says “his division was on duty” at the temple (Lk. 1:8). Duty is Monday talk. That day the lot fell on Zechariah to go into the temple to offer prayers and burn incense. And when he did he saw an angel. The angel told him his barren wife would give birth to a son. He was to name him John. It was an exceptional moment. But Zechariah didn’t arrive at that moment because he was having an exceptional day. He hadn’t specially prepared to receive a miracle from God that day. It wasn’t at a healing conference or a prayer retreat. He wasn’t on a pilgrimage away from ordinary life. He was on duty. He arrived at this exceptional moment because he was living by his everyday rule: to be prepared for God to come on any day of the week, especially the first day of the week, even the first workday, should he so desire.

Maybe that’s why Zechariah was chosen to be the father of the prophet who would ‘prepare the way’ for God’s dawning future. Maybe all history was waiting for a father like Zechariah, a man of duty and everyday discipline, to raise a son like John, because John would have a special assignment. The angel told Zechariah his assignment would be to “make ready for the Lord a people prepared” (Lk. 1:17). Like father, like son:

“A voice crying out in the wilderness, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord!’” (Jn. 1:23).